Plot Summary: Wan Tin-Sau is a passionate but struggling actor who spends his days as a lowly extra while teaching acting at a community center. His path crosses with Piu-Piu, a nightclub hostess seeking acting lessons to better please her clients. As Tin-Sau's unwavering dedication to his craft faces constant humiliation, their unlikely connection becomes a journey of mutual healing, self-discovery, and the true meaning of perseverance in the face of failure.

Directors: Stephen Chow, Lee Lik-chi

Writers: Stephen Chow, Erica Li, Tsang Kan-cheung

Producers: Star Overseas Ltd. (Stephen Chow's company)

Music: Daisuke Hinata, Raymond Wong

Release Date: February 13, 1999

Box Office: HK$29,848,860 (Highest-grossing Hong Kong film of 1999)

Starring:

Stephen Chow as Wan Tin-Sau (尹天仇)

Cecilia Cheung as Lau Piu-piu (柳飄飄)

Karen Mok as Du Juan'er (杜娟兒)

Ng Man-tat as Mao (阿毛)

Jackie Chan as Extra (Special Cameo)

Introduction: More Than a Comedy, Not Quite a Tragedy

Stephen Chow's 1999 film King of Comedy (《喜劇之王》) stands as a watershed moment in the landscape of Hong Kong cinema and a pivotal work in the oeuvre of its creator. Released as a Lunar New Year film, it immediately captured the public imagination, becoming the highest-grossing domestic film of the year and triumphing over Jackie Chan's star-studded vehicle Gorgeous in a head-to-head box office battle.

Yet, its immediate commercial success belies its true significance. The film marks a profound artistic transition for Chow, a deliberate turn from the anarchic, nonsensical slapstick of his signature mo lei tau (無厘頭) style toward a more introspective, poignant, and layered comedy-drama. It is a work that finds humor in pathos and dignity in failure, telling the story of a struggling movie extra whose unwavering dedication to his craft is met with constant ridicule and humiliation.

The enduring power of King of Comedy lies in its deeply personal, semi-autobiographical core. The narrative is widely interpreted as a reflection of Chow's own arduous journey through the Hong Kong film industry, from his beginnings as a "temporary actor" (臨時演員) and host of a children's television program to his eventual ascension as the undisputed sovereign of Cantonese comedy.

This raw, personal honesty imbues the film with an emotional sincerity that transcends its comedic premise. While audiences came expecting the usual barrage of gags, they were met with a surprisingly heartfelt story about the pursuit of a dream, the vulnerability of love, and the quiet resilience of the human spirit.

The Anatomy of a Dream

The Passion of Wan Tin-Sau: An Actor Prepares

The film's protagonist, Wan Tin-Sau (尹天仇), played by Stephen Chow himself, is a character whose entire identity is consumed by his artistic ambition. He is a ke lei fe (茄喱啡), a Cantonese slang term for a movie extra or bit-part player, who also runs a small community center where he offers acting lessons to his neighbors.

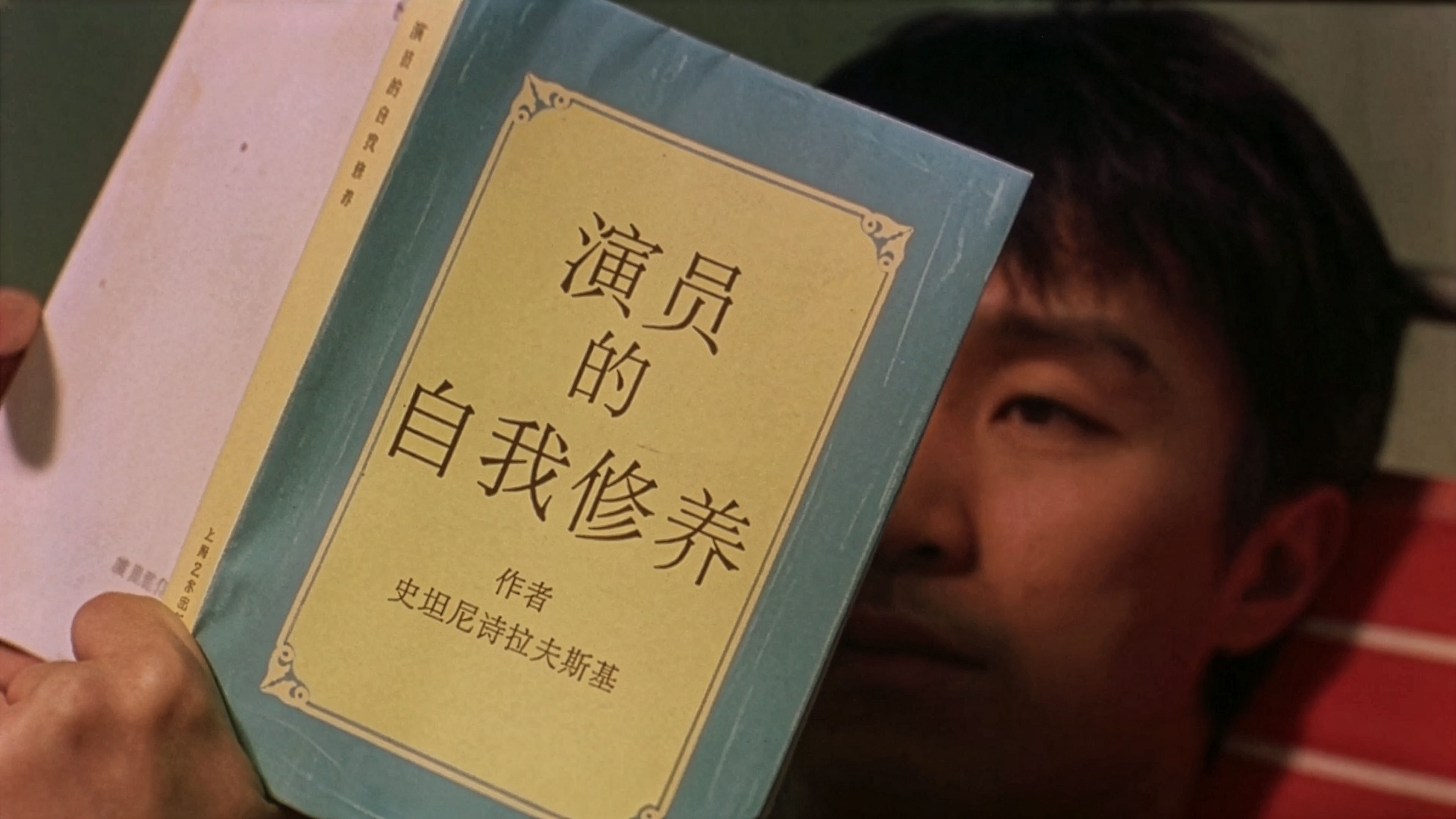

Despite his lowly status, his dedication to the craft is absolute, almost fanatical. This devotion is physically embodied by the book he carries with him everywhere: a well-worn copy of Konstantin Stanislavski's seminal text, An Actor Prepares (《演員的自我修養》).

This book is far more than a simple prop; it is Tin-Sau's scripture. It represents a pure, almost sacred belief in the art of acting as a noble pursuit, a stark contrast to the dismissive and purely commercial environment of the film sets where he works. The text was, in fact, a real textbook used by Stephen Chow during his own training days at the Hong Kong television network TVB, lending the character's obsession an air of lived experience.

Tin-Sau is constantly seen studying Stanislavski's theories, from "experiential art" (體驗藝術) to the complex process of working "from the outside in, then back out again" (由外入內再到外), attempting to apply these sophisticated techniques to roles that last mere seconds on screen.

This disconnect is the film's central tragicomic engine. Tin-Sau's professionalism is both his greatest virtue and the source of his perpetual humiliation. His insistence on finding psychological motivation for characters who are little more than set dressing is met not with admiration but with scorn, most notably from the hot-tempered lunchbox manager, Mao, who screams at him, "You're just an extra!"

The Vulnerability of Lau Piu-piu: The Making of a Star

If Wan Tin-Sau represents artistic purity, then Lau Piu-piu (柳飄飄) is the film's raw, emotional heart. A brash and beautiful nightclub hostess (舞小姐, mou siu je), she first seeks out Tin-Sau's acting lessons with a purely transactional motive: to learn how to feign innocence and charm to better please her clients and earn more money. Her character arc, from a hardened cynic to a woman capable of profound love and vulnerability, is the film's most powerful transformation.

This transformation is made all the more remarkable by the fact that the role was the cinematic debut of 18-year-old Cecilia Cheung. Discovered after appearing in a popular lemon tea commercial, Cheung had no prior acting experience. Her naturalism and unpolished rawness were essential to the character's authenticity. Piu-piu is a woman shielded by a tough exterior, a defense mechanism forged by a traumatic first love that left her deeply wounded.

The turning point in their relationship is a process of symbiotic healing. Each character possesses something the other desperately needs. Tin-Sau, for all his professional destitution, is emotionally open and sincere. Piu-piu, for all her worldly experience, is emotionally closed off. When Tin-Sau teaches her to "act," he is, in reality, providing her with a safe space to access the genuine emotions she has long suppressed.

Mirrors to the Industry: The Roles of Du Juan'er and Mao

The film's supporting characters serve as satirical but insightful reflections of the Hong Kong film industry's archetypes and power dynamics. Du Juan'er (杜娟兒), played by frequent Chow collaborator Karen Mok, is a reigning megastar who, unlike everyone else, recognizes the spark of genuine talent and dedication in Tin-Sau.

She represents the possibility that true artistry can be acknowledged within the commercial system, offering Tin-Sau his one shot at mainstream success. At the same time, her character also embodies the whims and capriciousness of stardom; she gives him his big break on a whim and is part of the system that ultimately snatches it away just as arbitrarily.

In stark contrast is Mao (阿毛), the irascible lunchbox manager (場務, cheung mou) played by another Chow regular, Ng Man-tat. He is the gatekeeper, the embodiment of the industry's working-class pragmatism and its casual cruelty towards those at the bottom. He is the one who denies Tin-Sau his lunchbox, a simple meal that becomes a powerful symbol of professional recognition and basic dignity.

His constant berating of Tin-Sau perfectly captures the daily humiliations faced by aspiring artists. The film's abrupt third-act reveal that Mao is actually an undercover C.I.B. agent in a jarring genre shift, but his initial role is a pitch-perfect depiction of the hostile environment that underdogs like Tin-Sau must navigate every day.

From Script to Screen: The Tumultuous Production History

The creation of King of Comedy was a process marked by serendipity, chaos, and an obsessive attention to detail that mirrored the film's own narrative themes of struggle and perseverance. Its production history is a story of last-minute changes, fortuitous encounters, and the intense cultivation of new talent, all of which contributed to the final film's unique texture and emotional depth.

Key Production Facts

Directors

Stephen Chow was the primary creative force, with Lee Lik-chi co-directing

Shooting Duration

Over 90 days, with multiple scenes requiring 30-40 takes

Location

Primarily shot in Shek O village, Hong Kong, including the Shek O Health Centre

Notable Change

The role of Mao was originally played by Anthony Wang before being recast with Ng Man-tat

The Real "King of Comedy": Autobiographical Origins

The film's narrative is deeply rooted in Stephen Chow's own life. Like his character, Chow's entry into the entertainment world was anything but smooth. He initially failed to get into TVB's prestigious acting classes (while his friend, future superstar Tony Leung Chiu-wai, was accepted) and began his career as an extra before eventually landing a job as the host of a children's television show, 430 Space Shuttle, for five years.

This commitment to authenticity extended to the creation of the protagonist. The character of Wan Tin-Sau was directly inspired by a real-life bit-part actor named Wu Jianhua, whose on-set moniker was "Xian Renqiu" (仙人求). Xian was brought onto the production as a consultant, and his real-life experiences and eccentricities heavily informed the character.

For certain scenes, the crew would ask Xian to perform them first, with Chow then observing and meticulously imitating his mannerisms, grounding Tin-Sau's quirky devotion in a tangible reality. Further embedding the film in cinematic history, the names of the three lead characters were lifted directly from two popular Hong Kong martial arts films from the 1960s, The Sacred Fire Command of Wulin and Buddha's Palm.

A Star is Born, A Role is Re-cast: The Casting Saga

The casting of King of Comedy was a tumultuous process that proved crucial to its success. A significant portion of the film's lengthy 90-plus day shoot was dedicated to its female lead, the complete newcomer Cecilia Cheung. With no prior film experience, Cheung struggled with the technical aspects of acting, including unclear pronunciation, poor intonation, and improper breath control.

The directors had to guide her meticulously, often giving her line-by-line instructions and reshooting every single one of her shots more than ten times. Her audition, however, was flawless. Co-director Lee Lik-chi had her perform a scene from the Japanese drama Long Vacation, and she passed with flying colors in just three takes with no errors.

Perhaps the most legendary piece of production lore is the cameo by Jackie Chan. In a moment of pure serendipity, Chow's King of Comedy and Chan's romantic comedy Gorgeous were filming at the same time in the same Sai Kung studio.

The two superstars, both of whom had famously started their careers as extras, agreed to make guest appearances in each other's films. This resulted in the classic scene where Chan, playing an extra, receives some unsolicited acting advice from the "expert" Tin-Sau. The friendly collaboration turned into a box office rivalry when both films were scheduled for release during the 1999 Lunar New Year holiday.

Decoding the Dialogue: Language, Culture, and Lasting Memes

To fully appreciate King of Comedy is to understand its deep roots in Cantonese language and Hong Kong culture. The film's dialogue, its central motifs, and even its on-set jargon resonated so powerfully with audiences that they transcended the screen, influencing the popular lexicon and creating new forms of cultural expression across the Chinese-speaking world.

The Gospel of an Actor: 《演員的自我修養》 (An Actor Prepares)

The film's most important cultural artifact is Stanislavski's book, An Actor Prepares. Before 1999, this foundational text of method acting was an obscure work in the Chinese-speaking world, known only to theater professionals and drama students. King of Comedy single-handedly propelled the book into the public consciousness, transforming it from an academic text into a pop culture icon.

Cultural Impact: The "Self-Cultivation" Meme

The title of the book, 《演員的自我修養》 (Yin yun di ji go sau yeung, "The Self-Cultivation of an Actor"), became a ubiquitous meme template. The phrase "The Self-Cultivation of a..." (《XX的自我修養》) entered the vernacular as a popular catchphrase, used humorously or seriously to describe the essential qualities, mindset, or professional ethics required for any given role or job:

《程序員的自我修養》

The Self-Cultivation of a Coder

《粉絲的自我修養》

The Self-Cultivation of a Fan

《老闆的自我修養》

The Self-Cultivation of a Boss

This is arguably the film's most widespread and enduring cultural legacy, a testament to its ability to distill a complex idea into a universally relatable symbol.

The Nuances of Nonsense: A Departure from Mo Lei Tau (無厘頭)

Stephen Chow's fame was built on his mastery of mo lei tau (無厘頭), a unique brand of Cantonese comedy that is notoriously difficult to translate. The term literally means "no source" or "makes no sense," and the humor is characterized by anarchic slapstick, nonsensical dialogue, deliberate anachronisms, fourth-wall breaks, and a heavy reliance on Cantonese puns and wordplay.

King of Comedy marks a deliberate departure from this style, offering instead a more restrained, character-driven approach to humor. While the film still contains moments of physical comedy and absurdist elements (particularly in its third-act genre shift), these are subordinated to the emotional journey of its protagonists. This tonal shift was a conscious artistic decision by Chow, who wanted to demonstrate his range and create something with greater emotional resonance.

The film's ability to balance comedy with genuine pathos was revolutionary for Hong Kong cinema at the time. It demonstrated that a commercial comedy could also be a vehicle for sincere emotional storytelling, paving the way for Chow's later works like Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle, which similarly blended spectacular comedy with surprisingly affecting character arcs.

This evolution in Chow's artistic approach coincided with significant changes in Hong Kong cinema and society. Released just two years after the handover to China, the film can be read as reflecting the anxieties and aspirations of a city in transition, navigating between commercial pressures and artistic integrity, between global ambitions and local identity.

Iconic Lines That Defined a Generation

"我養你啊!" ("I'll support you!") - Perhaps the film's most famous line. After Tin-Sau and Piu-piu spend the night together, his insecurity leads him to treat the encounter as a transaction, awkwardly offering her money. When she leaves hurt, he chases after her and shouts this declaration of lifelong commitment. Coming from a man with no money, no job, and no prospects, the line is stripped of all material meaning—it is a promise of his entire self, the only thing of value he has to give. This contrast between his material poverty and emotional richness makes the line a pinnacle of cinematic romance.

"前面漆黑一片,乜都睇唔到。"... "都唔係嘅,天光之後就會好靚㗎啦。" ("It's pitch black up ahead, can't see a thing."... "Not necessarily. It will be beautiful after daybreak.") - This quiet exchange as they sit on the beach looking at the dark sea carries metaphorical weight. Released just two years after Hong Kong's handover to China and during the Asian Financial Crisis, this dialogue about finding hope in darkness resonated deeply with the collective anxiety about the future.

"努力!奮鬥!" ("Effort! Struggle!") - Shouted by Tin-Sau towards the vast, indifferent sea in the film's opening shot, this two-word phrase serves as his personal mantra and the film's thesis statement. It perfectly encapsulates the aspirational "Hong Kong spirit" of that era—the deeply ingrained belief that hard work and perseverance can lead to success against all odds.

From Set Jargon to Public Slang: "Ling Bento" (領便當)

One of the film's most unique linguistic contributions was popularizing a piece of internal industry jargon. In Hong Kong film production, extras whose characters are finished for the day—often because their character has been killed off—would collect their boxed meal, or bento (便當), and go home. The film repeatedly visualizes this process, with Tin-Sau often being so insignificant that he is denied even this basic provision.

Through its memorable depiction, the film took the phrase "領便當" (ling bento, "to collect a lunchbox") and launched it into the mainstream. It is now a universally understood euphemism and internet slang term across Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mainland China for a character being killed off, fired, or otherwise written out of a narrative.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of a True Classic

Ultimately, the film's most enduring legacy may be its profound and lasting impact on the language and culture of its audience. Through its iconic lines, its popularization of industry jargon, and its transformation of an obscure acting textbook into a pop culture symbol, King of Comedy gave a generation a new vocabulary to articulate their own hopes, struggles, and aspirations.

The film's central, recurring image is that of Wan Tin-Sau's desperate quest for a simple lunchbox—a token of payment, yes, but more importantly, a symbol of basic professional respect and recognition. This simple, powerful metaphor encapsulates the film's enduring message: that in a world that often measures worth by success and status, the true struggle is for the acknowledgment that one's effort, however humble, has value.

It is a struggle that continues to resonate, making King of Comedy a classic of Hong Kong cinema and a masterpiece of humanist filmmaking. Stephen Chow's semi-autobiographical journey from extra to icon continues to inspire audiences more than two decades after its release, speaking to anyone who has ever pursued a dream in the face of ridicule, rejection, and seemingly insurmountable odds.

Through the perfect balance of laughter and tears, King of Comedy achieves what its protagonist so desperately sought: it finds dignity in failure and humanity in persistence. It is, in the truest sense, a comedy with heart—a film that understands that sometimes the most profound truths about the human condition can be found in the humble struggles of those society overlooks.

Comments

Post a Comment